The Lord Jehovah is the Lord of Hosts, the Lord mighty in battle. We know him in our day as Jesus Christ, our Savior and Redeemer. In some situations, the Lord has used the elements: the wind, the rain, and great hailstones to protect his people and to fight his battles. During the United State’s Revolutionary War, the Lord shaped the outcome of the conflict and the history of our nation and of the world by shifting the volume and direction of the wind.

Setting the Trap

It seemed that there was no possible way America could win its War of Independence! The British, with their highly trained armies and overwhelming naval control of the seas, were believed to be invincible. The rag-tag, at first untrained American army, lost battle after battle, and for years were on the run before the relentless British onslaught. The unborn country was severely divided, with many American tories who still professed allegiance to the British King.

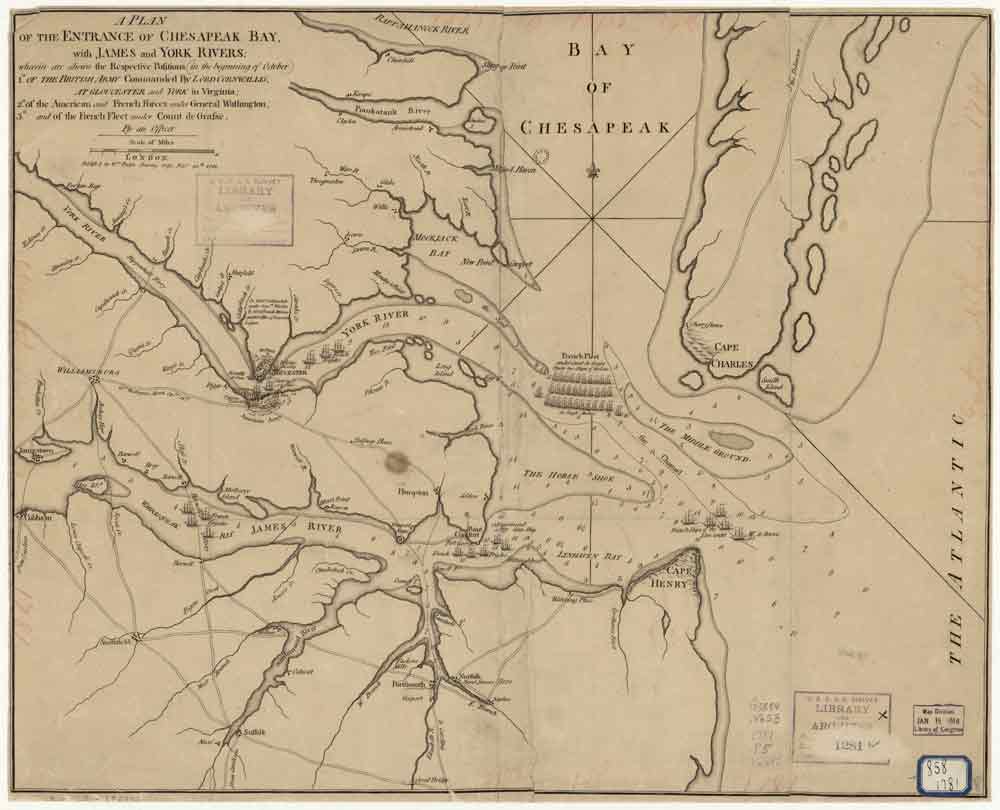

General George Washington’s main adversary was Major General Lord Charles Cornwallis. Over a five-year period, his armies defeated the Americans in numerous battles. Finally, In 1781, after a victorious two-year campaign in America’s south, General Cornwallis took his troops to Yorktown, in southern Virginia. This is the location where the York River flows into the Chesapeake Bay and enabled the English forces to be re-supplied by British ships from their West Indian fleet.

But then, in a daring strategic move, General Washington sought to trap and lay siege to Cornwallis and his troops at Yorktown. He would summon French ships from the East Indies to cut off the English supply ships, and while they were coming, he would transport thousands of his troops all the way down from New York to southern Virginia, hundreds of miles to the south, moving by land and by small boats down through the Chesapeake Bay.

Perhaps the Lord of Hosts intervened at this point to help bring the struggling American nation to its birth. What history uniquely shows to be the most pivotal battle of the American Revolution didn’t even involve American troops—it involved only French and English ships.

Two British Mistakes

Fourteen British ships sailed north to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on August 25th, but finding no French ships there, and seriously underestimating the urgency of the situation, the ships sailed further north to join with the rest of the British fleet under the command of Sir Thomas Graves. Admiral Graves had only five additional ships available to return with the 14 ships in the British fleet to resupply and defend General Cornwallis.

In the meantime, on August 29th, French Rear Admiral Comte de Grasse arrived in Chesapeake Bay with 27 ships of the line and three regiments of French troops. The British had already made two fatal mistakes: (1) they had failed to track the movements of the French fleet, and (2) they had badly underestimated the strength of the French fleet and had sent an inadequate force to deal with it.

When the British fleet of 19 ships arrived back at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay, on September 5th, they found 24 French ships at anchor behind Cape Henry, with the French busily disembarking their troops. With the wind and the tides, and the element of surprise in their favor, the British could have sailed in and inflicted heavy damage on the French ships. However, the conventional naval tactics of the time called for fleets to form up in lines of battle, so the English ships chose to line up outside the Bay, allowing the French time to hoist their anchors and form their own battle lines.

But then, as the battle had just begun, the wind suddenly died. The two lines of ships drifted southward, in sight of each other but unable to engage, for four days.

Then, on September 9th, as the wind freshened, it caught the French sails first. The French vessels were able to turn around and beat the English ships back to the entrance of Chesapeake Bay, successfully blockading it so the English couldn’t penetrate and resupply Cornwallis. Recognizing the futility of attacking the French fleet in their defensive formation, the British fleet gave up and sailed back to New York, leaving Cornwallis without any hope of resupply or rescue.

Did the Lord of Hosts becalm those winds, then freshen them first for the French? What a simple but unique way to control a battle, and thus control the fate of a nation!

The Siege Against Starving British Troops

Finally, on September 28th, Washington and his army, reinforced by French troops, arrived outside of Yorktown and began to lay siege against Cornwallis and his army. After three weeks, knowing that no supplies would be arriving, Cornwallis surrendered his starving force of 7,500 men—about a quarter of all the British forces in the American colonies.

And then, how simple it must have been for the Lord of Hosts to influence the hearts and attitudes of a few key men!

The British war with America was being led and ram-rodded by a war hawk—Lord North, the British Prime Minister. When he learned of Cornwallis’s defeat and surrender, he threw up his hands in disgust and resigned his political position. When his replacement was named by King George, his successors in England decided it was no longer in Britain’s best interest to prolong the seven-year-old war. They withdrew the rest of the British troops from the American mainland, and treaty negotiations were undertaken.

The British eventually signed the Treaty of Paris, which recognized the United States as a nation, and they agreed to remove all British troops from all American territories.

The Treaty of Paris—America recognized as a nation

How to end a long war, establish a land chosen above all lands, and forever change the course of history? If this was the workmanship of the Lord of Hosts, all it took was calming the winds for several days, and changing the minds and hearts of a few English politicians, and the impossible war for American independence was won!